Modeling reinforcement learning (Part III): Fitting the Kalman filter with Thompson sampling model

It’s been way too long, but here is the third post in a series to describe how to fit reinforcement learning models to data collected from human participants. Using example data from M. Speekenbrink and Konstantinidis (2015), in the series, we will go through all the steps in defining the model, estimating its parameters, and doing inference and model comparison.

In this post, we will focus on the Kalman filter + Thompson sampling model, which I wasn’t able to fit into the previous post, which covered the Kalman Filter with softmax and UCB rule. I will keep this post focused on this model, and then we will go into model comparison in the next post. I will assume you have read the previous two posts, so we can get straight into things. We’ll use the same dataset as before:

dat <- read.csv("https://github.com/speekenbrink-lab/data/raw/master/Speekenbrink_Konstantinidis_2015.csv")

tdat <- subset(dat,id2==4)

and use the Kalman filter code from the previous post:

kalman_filter <- function(choice, reward, noption, mu0, sigma0_sq, sigma_xi_sq, sigma_epsilon_sq) {

nt <- length(choice)

no <- noption

m <- matrix(mu0,ncol=no,nrow=nt+1)

v <- matrix(sigma0_sq,ncol=no,nrow=nt+1)

for(t in 1:nt) {

kt <- rep(0,no)

kt[choice[t]] <- (v[t,choice[t]] + sigma_xi_sq)/(v[t,choice[t]] + sigma_xi_sq + sigma_epsilon_sq)

m[t+1,] <- m[t,] + kt*(reward[t] - m[t,])

v[t+1,] <- (1-kt)*(v[t,] + sigma_xi_sq)

}

return(list(m=m,v=v))

}

Thompson sampling

Thompson sampling is a probabilistic decision strategy, which can be implemented by drawing a sample for each option from what I have been calling the prior predictive distribution of the expected reward of that option, and then picking the option with the highest sampled value. This is the same as picking an option according to the (subjective) probability that the option has the highest expected value on the current trial.

Estimation with sampling

The sampling nature of Thompson sampling makes it easy to implement. If we have a (pseudo) random number generator, we can just sample values for each option, and determine the option with the maximum sampled value, like we did in the first post.

But let’s pause for a moment. While it is easy to construct an artificial agent who behaves in this way, when we observe the choices of such an agent, we don’t have immediate access to the sampled values that led to each particular choice. So while we can sample values for our own artificial agent, the samples we obtain may not match those of the actual agent we want to model. That means that while our own simulated agent might have obtained samples that forced her to choose option 2 at trial 10, the agent we want to model might have obtained samples that forced her to choose option 4 at trial 10. When taking an “outside view” of an agent, we need to consider all possible samples that they could have obtained. We can’t just use one particular sample and pretend that is the same one the agent obtained.

In short, what we truly care about is the probability that an agent

samples, for each option, a value that is higher than the value of all

the other options. To approximate that probability, we could repeat the

sampling process many times, and determine the proportion of times that

each option was the highest. So even though we might assume that the

agent draws a single value for each option, in order to accurately model

that agent, we should draw (many) more samples. The following code

calculates choice probabilities for a Thompson sampling strategy by

generating nsample replications of that procedure for each trial.

thompson_choice_prob_sampling <- function(m, v, nsample) {

# m is a vector with prior predictive means

# v is a covariance matrix for the prior predictive distributions

# nsample is an integer

# initialize a matrix for the choice probabilities

prob <- matrix(0.0,ncol=ncol(m),nrow=nrow(m))

# loop through all trials

for(t in 1:nrow(m)) {

# generate samples

mtilde <- matrix(rnorm(nsample*ncol(m), mean = m[t,], sd = sqrt(v[t,])), nrow=nsample, byrow = TRUE)

# determine maximum

max <- apply(mtilde, 1, which.max)

# loop through all options to calculate proportion of maximum

for(i in 1:ncol(m)) {

prob[t,i] <- sum(max==i)/nsample

}

}

return(prob)

}

We can use this sampling procedure to define a function to calculate the log likelihood as follows. Note that, as we did before, we assume variance parameters are provided on a log scale, which are then transformed back to a positive value through exponentiation:

kf_thompson_negLogLik_trans_sampling <- function(par, data, nsample=1000) {

# set parameters

mu0 <- par[1]

# transform variances back to > 0

sigma0_sq <- exp(par[2])

sigma_xi_sq <- exp(par[3])

sigma_epsilon_sq <- exp(par[4])

# set variables

choice <- data$deck

reward <- data$payoff

# run Kalman filter (defined earlier)

kf <- kalman_filter(choice,reward,4,mu0,sigma0_sq,sigma_xi_sq,sigma_epsilon_sq)

# extract means and variances

m <- kf$m

v <- kf$v

# calculate choice probabilities from these

p <- thompson_choice_prob_sampling(m, v, nsample)

# calculate likelihood of observed choices

lik <- p[cbind(1:nrow(data),choice)]

# transform into negative log likelihood

negLogLik <- -sum(log(lik))

# to avoid issues with numerical optimization routines, set to very high value if

# something goes wrong

if(is.na(negLogLik) | negLogLik == Inf) negLogLik <- 1e+300

return(negLogLik)

}

Applying this to our dataset, we get the following results:

set.seed(20210521)

kf_thompson_negLogLik_trans_sampling(c(0,log(1000),log(16),log(16)), data=tdat)

## [1] 121.8371

If we were to run this again with a different random seed, we would however get slightly different results:

set.seed(1)

kf_thompson_negLogLik_trans_sampling(c(0,log(1000),log(16),log(16)), data=tdat)

## [1] 121.3463

Such variability is inherent in any sampling procedure. In addition to the noisiness of sampling, there is also an issue of resolution. When we sample n = 1000 samples, our possible estimates of the probability p(m̃1 > m̃2) are $\frac{0}{1000}, \frac{1}{1000}, \ldots \frac{999}{1000}, \frac{1000}{1000}$. There are thus no more than 1001 possible estimates of this probability. That seems like a reasonable number, but if we are to discern between a model with p = .9071 and a model with p = .9074, that level of resolution is not satisfactory. Using 1000 samples, we could never obtain an a result where 907.1 samples are higher for option 1 than for option 2. It is also quite likely that for small probabilities, the estimate would turn out to be 0. This will be problematic when a choice was actually made for which our predicted probability is 0, as it would make the likelihood of the whole sequence of choices to be 0.[1] We can increase the number of samples to e.g. 10,000 to get better resolution, but there is still variability:

set.seed(20210521)

kf_thompson_negLogLik_trans_sampling(c(0,log(1000),log(16),log(16)), data=tdat, nsample=10000)

## [1] 121.8062

set.seed(1)

kf_thompson_negLogLik_trans_sampling(c(0,log(1000),log(16),log(16)), data=tdat, nsample=10000)

## [1] 121.7084

Many of the common numerical optimization routines (as e.g. implemented

in R’s optim function) expect the objective function to be

deterministic, rather than a noisy probabilistic function. Hence, using

something like kf_thompson_negLogLik_trans_sampling in a call to

optim may not provide the desired results.

While we now know of the potential pitfalls, which will be dealt with soon, let’s estimate the model with this sampling approach. I’m also calculating the running time, for comparison with the later (more precise) approach:

set.seed(20210521)

# Start the clock!

ptm <- proc.time()

# estimate

est <- optim(c(0,log(1000),log(16),log(16)), kf_thompson_negLogLik_trans_sampling, data=tdat)

# Stop the clock

proc.time() - ptm

## user system elapsed

## 60.012 0.068 60.300

The results are:

est

## $par

## [1] -7.17389770 4.41825582 -0.04023475 -2.04946301

##

## $value

## [1] 48.76474

##

## $counts

## function gradient

## 87 NA

##

## $convergence

## [1] 10

##

## $message

## NULL

And transforming the estimated parameters to the correct scale gives:

est_pars <- c(est$par[1],exp(est$par[2:4]))

names(est_pars) <- c("mu0","sigma0_sq","sigma_xi_sq","sigma_epsilon_sq")

est_pars

## mu0 sigma0_sq sigma_xi_sq sigma_epsilon_sq

## -7.1738977 82.9514766 0.9605639 0.1288041

If we run this again with a different random seed, we get the following results:

set.seed(1)

# Start the clock!

ptm <- proc.time()

# estimate

est <- optim(c(0,log(1000),log(16),log(16)), kf_thompson_negLogLik_trans_sampling, data=tdat)

# Stop the clock

proc.time() - ptm

## user system elapsed

## 340.174 0.280 341.459

est

## $par

## [1] -3.75913819 4.17943772 0.03514012 -3.73192832

##

## $value

## [1] 50.96787

##

## $counts

## function gradient

## 501 NA

##

## $convergence

## [1] 1

##

## $message

## NULL

est_pars <- c(est$par[1],exp(est$par[2:4]))

names(est_pars) <- c("mu0","sigma0_sq","sigma_xi_sq","sigma_epsilon_sq")

est_pars

## mu0 sigma0_sq sigma_xi_sq sigma_epsilon_sq

## -3.75913819 65.32910978 1.03576483 0.02394661

You can see that the estimates are quite different. That is because

whilst sampling is straightforward to implement, it is inherently noisy.

If we were to implement Thompson sampling within an estimation routine,

that means that we will probably get a different likelihood every time

we run the routine with exactly the same parameters. Such noise in the

likelihood is not something that most numerical optimization routines

can deal with very well. While certain techniques, such as Bayesian

optimization, work well with noisy

objective functions,[2] traditional maximum likelihood estimation

assumes that the likelihood has a fixed value for every set of parameter

values. It is therefore strongly recommended that, where possible, you

work out the probabilities analytically (or at least numerically with a

good level of precision). If sampling is unavoidable, then you should

aim to implement procedures to make the evaluations of the likelihood as

stable as possible. That means using as large a number of samples as

possible. Also, you could use the same random number seed every time you

call the objective function within a numerical optimization routine

(e.g. set the seed within the kf_thompson_negLogLik_trans_sampling

function). Whilst this will make the results dependent (to some extent)

on an arbitrary choice of a random number seed, it will make the

objective function behave like a deterministic function, which can help

the numerical optimization routine find a minimum.

Analytical derivation

In the case of Thompson sampling, it is possible to derive the probabilities analytically. As in the previous post, we will denote a sample from the prior predictive mean of option j on trial t as

\[\tilde{m}_{t,j} \sim \mathcal{N}(m_{t-1,j},v_{t-1,j} + \sigma^2_\xi)\]The first step is to think of the samples from the options as coming from a multivariate distribution. As we are using the Kalman filter, for which the posterior distributions of the means are Normal, this is a multivariate Normal distribution:

\[\tilde{\mathbf{m}}_{t} \sim \mathcal{N}\left(\mathbf{m}_{t-1},\mathbf{V}_{t-1} + \text{diag}(\sigma^2_\xi)\right)\]Here, \(\tilde{\mathbf{m}}_t = (\tilde{m}_{t,1}, \ldots, \tilde{m}_{t,K})\) is a vector of samples for each option, mt − 1 is the vector of posterior means at trial t − 1 for each option, and Vt − 1 is the covariance matrix of the posterior means (at trial t − 1) for all options. As the posteriors for the options are independent, the covariances are all 0, so this is a diagonal matrix, with vt − 1, j on the diagonal:

\[\mathbf{V}_{t-1} = \text{diag}(v_{t-1})\]As before, because of the time-varying means, we need to add σξ2 to these to get the variance of the prior predictive distribution of the means at trial t. Again, because of the independence of the options, this is a diagonal matrix diag(σξ2).

(At this point, you might wonder why we don’t just use independent Normal distributions, rather than a multivariate distribution. The reason for this will become clear shortly.)

The next step is to realise that the sample from one option, say option 1, is larger than all the other samples if each pairwise difference is greater than zero: m̃1, t − m̃j, t > 0, j ≠ 1. If there are K options, we need to consider K − 1 of such pairwise differences. You can think of these pairwise differences as a set of derived new variables which are a linear transformation of the original variables. To make this a bit more intuitive, let’s start with a situation with only two options (i.e. K = 2). For two options, we sample

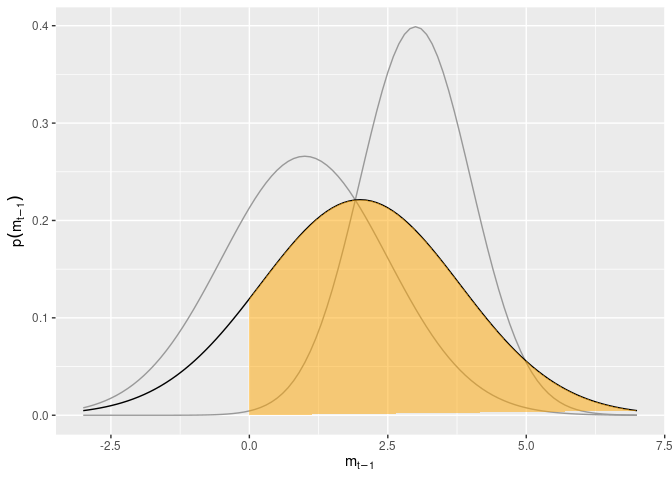

\[\begin{aligned} \tilde{m}_{1} &\sim \mathcal{N}(m_1,v_1) \\ \tilde{m}_{2} &\sim \mathcal{N}(m_2,v_2) \\ \end{aligned}\]Now, m̃1 is larger than m̃2 whenever m̃1 − m̃2 > 0. It is a well-known fact that the sum of two Normal-distributed variables is also a Normal-distributed variable, with a mean equalling the sum of the means of the two variables, and a variance equalling the sum of the variances of the two variables. In our case, the mean of the sum m̃1 + m̃2 would be m1 + m2, and the variance of this random variable would be v1 + v2. It is also a well-known fact that a Normal-distributed variable multiplied by a scalar b also follows a Normal distribution, with mean equalling the mean of the variable multiplied by that scalar, and variance equalling the variance of the variable multiplied by the absolute value of the scalar. For instance, the distribution of − 1 × m̃1 has a mean of − m1 and a variance of | − 1| × v1 = v1. Combining these two well-known facts, the distribution of the difference becomes

\[\tilde{m}_1 - \tilde{m}_2 \sim \mathcal{N}(m_1 - m_2, v_1 + v_2)\]i.e. another Normal distribution. The plot below shows an example for a relatively certain high option, and a less certain low option. It also depicts as the shaded region the probability that the higher option is indeed better than the lower option.

library(ggplot2)

minX <- -3

maxX <- 7

tdat <- data.frame(x=c(0,seq(0,maxX,length=100),0),

y = c(0,dnorm(seq(0,maxX,length=100),mean=3-1,sd=sqrt(1.5^2+1)),0))

ggplot() + geom_function(fun=function(x) dnorm(x,mean=1, sd=1.5), col=grey(.6)) + geom_function(fun=function(x) dnorm(x,mean=3), col=grey(.6)) + geom_function(fun=function(x) dnorm(x,mean=2,sd=sqrt(1.5^2 + 1))) + xlim(minX,maxX) + geom_polygon(aes(x=x,y=y),data=tdat, fill="orange", alpha=.5) + xlab(expression(m[t-1])) + ylab(expression(p(m[t-1])))

To generalize this to situations with more than two options, we need to consider all difference scores between a focal option and the other ones simultaneously. For instance, the probability that option 1 (out of 4) has the highest expected reward is the probability that m̃t, 1 = m̃t, 2 > 0, and m̃t, 1 = m̃t, 3 > 0, m̃t, 1 = m̃t, 4 > 0. To compute this probability, then, we need to consider three difference scores simultaneously as a multivariate variable, and then integrate over the range from 0 to ∞ on all dimensions. Luckily, this new multivariate variable is a linear transformation of $\tilde{\mathbf{m}}_{t}$. This makes things easier, as a linear transformation of a multivariate Normal variable also follows a multivariate Normal distribution. Let’s focus on the first option, and consider (as in the experiment) the case of a 4-armed bandit. We can get the required difference scores as

\[\tilde{d}_{t-1,1} = \mathbf{A}_1 \cdot \tilde{\mathbf{m}}_{t-1}\]with

\[\mathbf{A}_1 = \left[ \begin{matrix} 1 & -1 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & -1 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & -1 \end{matrix} \right]\]This is a linear transformation of a multivariate Normal variable, which makes it straightforward to derive that the distribution of the difference scores is:

\[\tilde{d}_{t-1,1} \sim \mathcal{N}\left(\mathbf{A}_1 \cdot \mathbf{m}_{t-1}, \mathbf{A}_1 \cdot (\mathbf{V}_{t-1} + \text{diag}(\sigma^2_\xi) ) \cdot \mathbf{A}^\top_1\right)\]To work out the probability that option 1 has the highest mean, we need

the inverse of the cumulative multivariate distribution evaluated at

0, just like in the example of the 2-option case. Unfortunately,

there is no closed-form definition of this cumulative distribution, and

hence we will have to rely on numerical computation. The mvtnorm

package provides the pmvnorm function for this purpose. Three

algorithms are provided. Here, I use the Miwa option, as the default

GenzBretz option is partly random. The following code implements the

calculation of the Thompson sampling strategy for four options. It is

straightforward to generalize this to more or less options, but be aware

that each evaluation of pmvnorm takes some time, and hence the

function is not fast.

# load the mvtnorm package

library(mvtnorm)

# function definition

thompson_choice_prob <- function(m,v) {

# m is a vector with prior predictive means

# v is a covariance matrix for the prior predictive distributions

# construct the transformation matrix for the difference scores for the first option

A1 <- matrix(c(1,-1,0,0, 1,0,-1,0, 1,0,0,-1), nrow = 3, byrow = TRUE)

# construct an array to contain the transformation matrices for all options

A <- array(0,dim=c(3,4,4))

A[,,1] <- A1

# transformation of each other option is just a shuffle of the one for option 1

A[,,2] <- A1[,c(2,1,3,4)]

A[,,3] <- A1[,c(2,3,1,4)]

A[,,4] <- A1[,c(2,3,4,1)]

# initialize a matrix for the choice probabilities

prob <- matrix(0.0,ncol=ncol(m),nrow=nrow(m))

# loop through all trials

for(t in 1:nrow(m)) {

# loop through all options

for(i in 1:4) {

# newM is the mean vector of the difference scores

newM <- as.vector(A[,,i] %*% m[t,])

# newV is the covariance matrix of the difference scores

newV <- A[,,i] %*% diag(v[t,]) %*% t(A[,,i])

# calculate the (inverse) cumulative probability with the Miwa algorithm. Note: this is slow!

prob[t,i] <- pmvnorm(lower=c(0,0,0), mean = newM, sigma = newV, algorithm=Miwa(steps=128))

# If there are any probabilities below 0 due to numerical issues, set these to 0

prob[prob<0] <- 0

}

}

return(prob)

}

Using this function, we can define a function to evaluate the negative

log Likelihood for this model, as we did in the last post. The following

function relies on transforming all variances by a log transformation,

so that we can later use optim for unbounded parameters.

kf_thompson_negLogLik_trans <- function(par,data) {

# set parameters

mu0 <- par[1]

sigma0_sq <- exp(par[2])

sigma_xi_sq <- exp(par[3])

sigma_epsilon_sq <- exp(par[4])

# set variables

choice <- data$deck

reward <- data$payoff

# run Kalman filter (defined earlier)

kf <- kalman_filter(choice,reward,4,mu0,sigma0_sq,sigma_xi_sq,sigma_epsilon_sq)

# extract means and variances

m <- kf$m

v <- kf$v

# calculate choice probabilities from these

p <- thompson_choice_prob(m,v)

# calculate likelihood of observed choices

lik <- p[cbind(1:nrow(data),choice)]

# transform into negative log likelihood

negLogLik <- -sum(log(lik))

# to avoid issues with numerical optimization routines, set to very high value if

# something goes wrong

if(is.na(negLogLik) | negLogLik == Inf) negLogLik <- 1e+300

return(negLogLik)

}

In the previous post, I discussed that the parameters of the Kalman filter, combined with a softmax or UCB rule, are not all identifiable. This is not a problem for the Kalman filter + Thompson sampling model. Indeed, multiplying the variances of the Kalman filter by a common scaling factor produces different likelihoods:

dat <- read.csv("https://github.com/speekenbrink-lab/data/raw/master/Speekenbrink_Konstantinidis_2015.csv")

tdat <- subset(dat,id2==4)

kf_thompson_negLogLik_trans(c(0,log(1000),log(16),log(16)),tdat)

## [1] 121.6625

kf_thompson_negLogLik_trans(c(0,log(20*1000),log(20*16),log(20*16)),tdat)

## [1] 278.1139

kf_thompson_negLogLik_trans(c(0,log(.002*1000),log(.002*16),log(.002*16)),tdat)

## [1] 1e+300

If you are interested in this issue of identifiability, I have written a (short) paper on it (Maarten Speekenbrink 2019).

As the model is identifiable, we can choose to estimate all the

parameters of the Kalman filter. This is what we do in the code below.

Note that it takes some time to complete (because the pmvnorm function

isn’t fast).

# Start the clock!

ptm <- proc.time()

# estimate

est <- optim(c(0,log(1000),log(16),log(16)), kf_thompson_negLogLik_trans, data=tdat)

# Stop the clock

proc.time() - ptm

## user system elapsed

## 169.642 0.275 170.948

Comparing the execution time, we can see that whilst this run is not as fast as the first time we tried optimizing the sampling version of the model, it is actually faster than the second time we ran the latter. So sampling is not necessarily faster and if we would have increased the number of samples to get more reliable results, it would probably be slower!

The results of this estimation are:

est

## $par

## [1] -25.60817110 5.83065928 0.03283952 -0.60806981

##

## $value

## [1] 47.17611

##

## $counts

## function gradient

## 281 NA

##

## $convergence

## [1] 0

##

## $message

## NULL

and transforming the parameters back to the right scale gives:

est_pars <- c(est$par[1],exp(est$par[2:4]))

names(est_pars) <- c("mu0","sigma0_sq","sigma_xi_sq","sigma_epsilon_sq")

est_pars

## mu0 sigma0_sq sigma_xi_sq sigma_epsilon_sq

## -25.6081711 340.5831440 1.0333847 0.5444007

As a cautionary note, I should mention that whilst the parameters of the Kalman filter + Thompson sampling model are identifiable in principle, with limited data, there may be practical issues of identifiability, and it is certainly not given that the estimates will be reliable…

Conclusion

Using simulation routines in deterministic optimization routines is not advisable. If you really have to rely on simulation to compute the likelihood, then use optimization routines that are designed to deal with noisy objective functions. And use the maximum number of simulations feasible to reduce the noise as much as possible. Whenever possible, it is better to avoid sampling and calculate the likelihood analytically.

References

Speekenbrink, M., and E. Konstantinidis. 2015. “Uncertainty and Exploration in a Restless Bandit Problem.” Topics in Cognitive Science 7: 351–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12145.

Speekenbrink, Maarten. 2019. “Indentifiability of Gaussian Bayesian Bandit Models.” In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Cognitive Computational Neuroscience, 686–88. https://doi.org/10.32470/CCN.2019.1335-0.

[1] Recall that the likelihood of a sequence of choices is the product of the likelihoods of each individual choice. If one element in such a product is 0, the whole product is 0.

[2] For a quick overview of some optimization algorithms in R which do handle noisy objective functions, you can have a look at this blog post

Comments